Each year, during those awkward days between Christmas and the new year, I adopt a planner with the intention of using it religiously — sort of an unintentionally reoccurring New Year’s resolution. And not unlike most New Year’s resolutions, I’ve never successfully seen it through. For long, I blamed the digital era. As if my Google Calendar, coupled with the Reminders App, made any form of physical planner just a relic from an analog past — like the invention of the smartphone cemented the watch’s fate as a fashion accessory rather than a practical tool.

But since my ADHD diagnosis, I’ve come to realize that my problem isn’t technology. It’s the fact that a main component of most organizational tools does not work for neurodivergent brains: too much imposed order caused by arbitrary rules and rigid lines. When you’re neurodivergent, the traits of originality and novelty tend to evade planners fixed in rigid systems. So I accepted my fate. I’d go on sporadically using my Google Calendar despite the fact that many of my most critical notes just can’t be simplified to “event” or “task.”

That is, until I discovered the Hobonichi Weeks Techno.

Many of us excel in creative problem-solving, often creating multiple solutions to a single problem. Our ability to think outside the box literally changes the world — from electric cars to music stuck in the collective consciousness for generations. Satoshi Tajiri is Autistic and, by connecting his special interest in bugs and creepy crawlies with his video game hobby, gave the world Pokemon.

As Dr. Amber Walser, an ADHD specialist, once explained to me:

“People with ADHD think outside the box. They’re comfortable being creative and sort of breaking or bending the rules in their thinking,” she said. “They’re really, really good about getting excited and fixated and energized by new and fresh ideas, because their brains don’t work with rules and I think the ADHD brain does a much better job at creativity. It is a superpower.”

Based on Dr. Walser’s logic, ordinary planners are the antithesis of the neurodivergent brain — they’re strict lines, compliance culture, and ultimately a one-size-fits-all system. The consequences of a planner, however, have the power to bleed off the pages and into the real world — paralysis by deadline, restructuring and emotional bottlenecking.

For my birthday last autumn, I acquired a “traveler’s notebook,” which is essentially a leather sleeve that holds together anything you can figure out how to bind with an elastic band — a level of customization I never knew I needed. Increasingly, I filled it, and increasingly, my bones ached for a planner. So despite my best instincts, I visited Papier, swearing that this time, bound by leather, it’d be different.

This particular Papier journal was your standard planner, but undated, meaning I had the honor of numbering my days on every page, which might sound like the soft structure I was looking for, until I realized how easy it was to repeat one date in January, not notice until reaching April — and, like a bad omen — the whole year’s ruined.

So there I was, venting about the whole ordeal to my cousin, a true planner-user. “I already bought my 2026 planner, but my whole TikTok feed is Hobonichi planners,” she told me, not knowing how much power her next words would hold. “Look it up. Looks really cute.”

And just like that, a new hyperfixation was born.

Upon searching “Hobonichi Weeks” on Amazon (because instant gratification), there were lots of adorable designs, which instantly excited me. But one was special. It featured the covers of a children’s novel, and as a writer myself, a literature reference was compelling, but this literature reference was it.

I read “The Little House” when I was young. It’s a story about a cottage in the countryside that finds comfort in watching the seasons change until a city encroaches on its peace, overwhelming it with urban sprawl. Thankfully, the great-great-granddaughter of its original builder rescues the little house by moving it atop a grassy hill to once again watch seasons change — a sweet motif for urban development, sure — but within the bounds of my leather journal, it’s a metaphor for the inevitable ebb and flow of the year ahead of me and within it.

After a lifetime of cracking under structure, I’ve finally begun to develop my human-centered design — a kind of chaos-friendly order that simultaneously satisfies my need for comfort and joy so I can best show up in the world.

Year At A Glance

One page in and BAM, you’re already faced with the entire year, all 12 months. Each has a few lines and a box for each day, void of instructions — an ambiguity that gives permission to customize for needs-led visual decluttering. This is where I decided I’d chronicle birthdays, so I can quickly lift the cover and discover whose celebration to prepare for next.

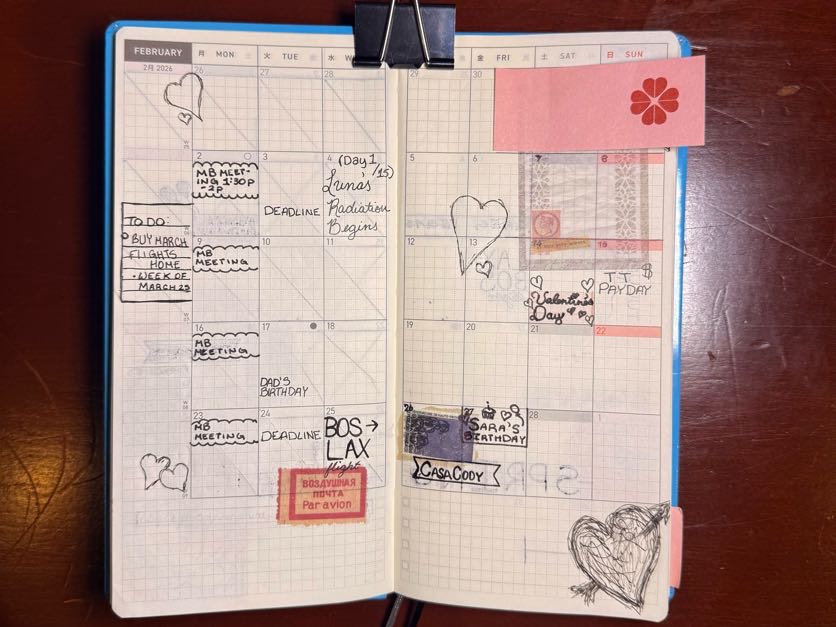

One Month At A Time

Get to flipping pages and you’ll find the months — one after the other — which helps avoid the micro-task burnout flipping through 28-31 days of pages before arriving at the next month. This way, I can easily plan and reference my entire year without the fatigue of facing blank weeks in between. Around the calendar is blank, grid space — void of prompts asking pointless questions like what I had for breakfast or logs to track my water intake… unless I want there to be.

It’s the exact kind of chaos-friendly order that satisfies my need for comfort and joy before taking on a task.

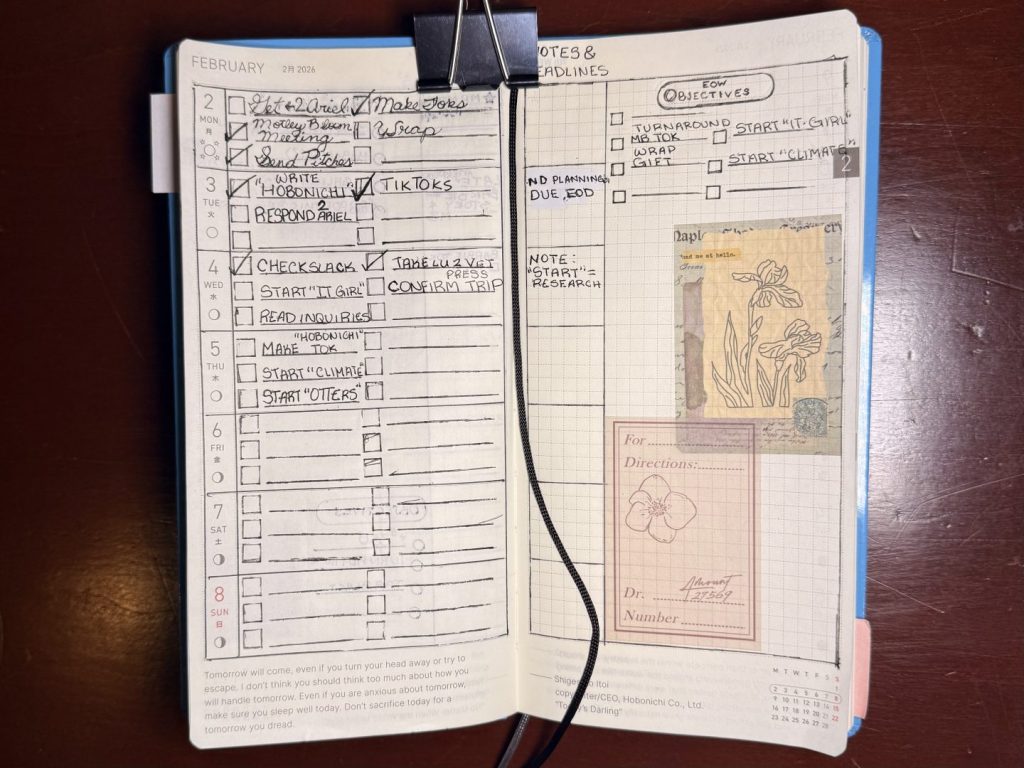

Days Of The Week

What’s special about these pages is their simplicity. They feature nothing more than what you need and leave space for what it’s missing — an amazing format for neurodivergent minds because no two weeks or days have to be the same. In fact, I’ve made an intentional, end-of-week ritual out of designing the week ahead. I grab my Alex Melnyk stencil from within its leather bounds and get to outlining the “days” boxes. On the right, I extend them, creating a section for “Notes + Deadlines,” so they don’t take up any precious to-do list space, and create check-lists for the aforementioned tasks I’m “to do.” In the empty grid space, I decorate the page with cute stickers and create lists — typically assigning one to “shopping” and another for “by Friday” objectives. By assigning these soft deadlines in a sidebar, goals and reminders enter the “intent without immediacy” part of my brain — they become ambient obligations, reducing the visual threat of a looming reminder for tomorrow or unfinished tasks of yesterday.

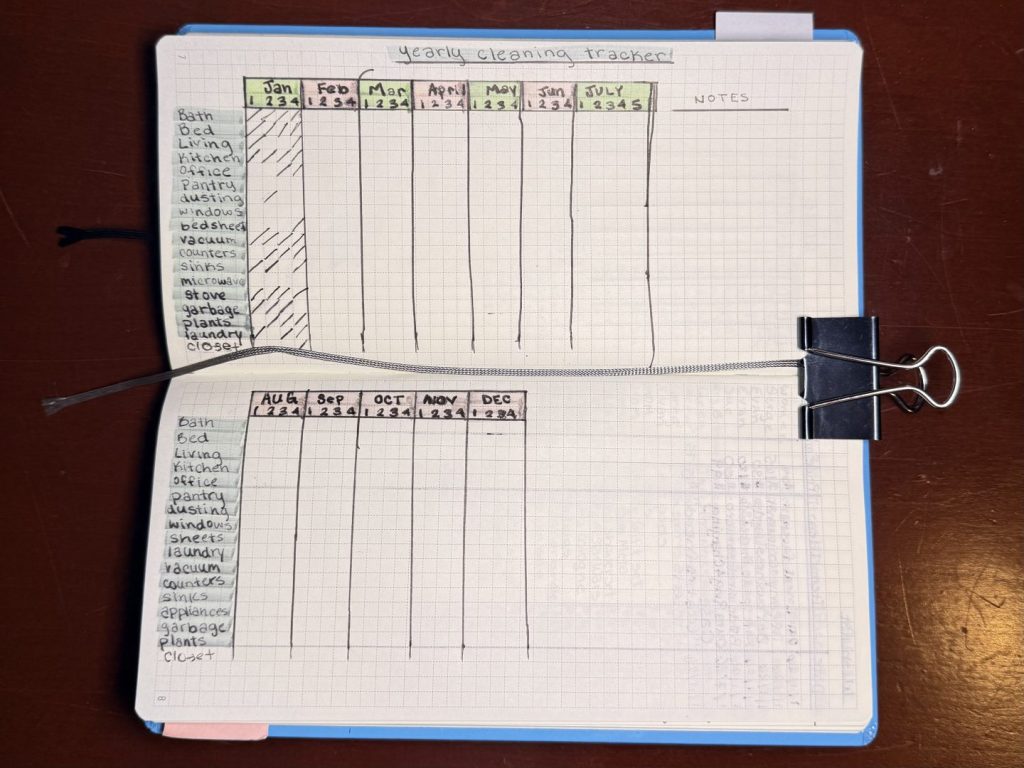

Logs Not Lists

You’ll notice that there are two strings hanging from the planner. Yes, they’re bookmarks — presumably intended for marking the relevant month and week at any given time, but I’ve decided to mark my month with a post-it tab, leaving one string for the current week and the other for a special and necessary page: my cleaning log.

In typical ADHD-fashion, tidiness has never been my strong suit. I’ve found that having a reminder that I can ignore, an alarm I can postpone or a calendar task staring me in the face with a judgy, empty checkbox makes me postpone the task more indefinitely than if I’d never been reminded in the first place. So I’ve turned toward logs. Lists often feel like impending doom — like a ticking time bomb that I dare not disarm. Logs, on the other hand, feel motivating — like so long as I do enough to comfort myself, I’ll be proud to look back on all their little marks.

Some other ways I fill these empty pages are with information: packing checklists for when I’m preparing an overnight bag, gift lists for when the perfect gift idea comes to mind and I don’t want to forget or lose on a random post-it note, a log for my different sources of income and write-offs so I’m not scrambling when tax-season comes around, as it so often does.

What’s On The Inside

For many of the girls on TikTok, it seems that there’s a whole world of external customization I’ve yet to scratch the surface of since my leather traveler’s notebook serves that purpose, but in my opinion, this little planner is materialistic proof that it really is what’s on the inside.

It’s funny — I always thought that I just couldn’t do planners. But as it turns out, most of them just don’t do it for me. My Hobonichi methods might not even be all that different from the many failed planners I’ve bought off the shelf, but perhaps, for neurodivergent people, what’s within the boxes and where they live on the page may not be the problem after all, but the fact that they exist. The pressure to conform to them. To follow their rules. The rebel in us defies that logic. The rebel in me always has at least. But this little Japanese planner gives me the freedom, not just to do what I want, but be who I am — and in turn, do what I have to.